Original: Nelly Luna Amancio, El Comercio, 1/8/06.

The Monastery of Santa Clara turned 400 this year. Its inhabitants, cloistered nuns, opened the doors to share its secrets.

Sor Rosa chatted online. And she did it without hesitation, and an enormous smile. Since 1999, when the Vatican allowed cloistered convents to use the Internet with"moderation and discretion," the sisters of the Monastery of Santa Clara, in the Barrios Altos district of Lima, have allied themselves with the web.

Now, Sor Rosa has e-mail and surfs. She looks for information about her convent and her order, the Poor Clares. She chats with other nuns at other sites and coordinates meetings. Sor Rosa Inmaculada is a globalized cloistered nun.

The other 45 nuns at the Monastery have also joined the information highway. They listen to news broadcasts, watch TV, once in a while rent movies (the last one they saw was "The Passion of the Christ") and if they wanted, they could use cell phones. But, of course, no telenovelas (television soap operas) are allowed, although once in a while one of the naughty novice sisters has been known to sneak a peek at an episode of the most current one.

Everything in moderation.

The nuns say they don't neglect contemplation. They made a decision to retire from the external world, to isolate themselves and withdraw into prayer. In keeping with their Franciscan spirituality, they renounce all their material possessions. That is how the Poor Clare sisters live in Barrios Altos: in the most absolute austerity.

They make turrones, panetones, and other sweets to offer for sale in local markets. And from that income they manage to survive. That is how the nuns at this Monastery have been living for the past four hundred years, since Toribio de Mogrovejo founded it on January 4, 1606.

Four centuries of history, art, and tradition.

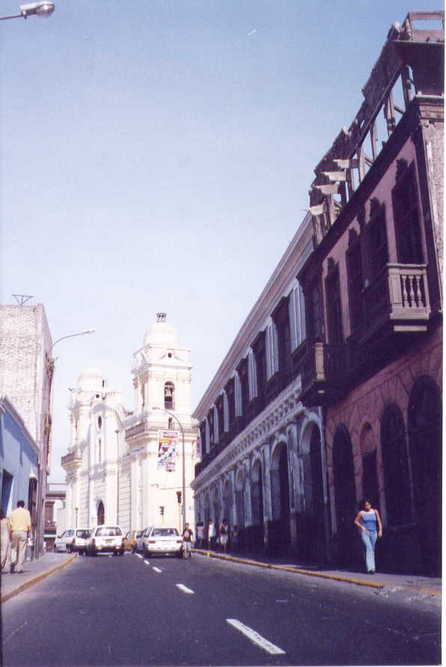

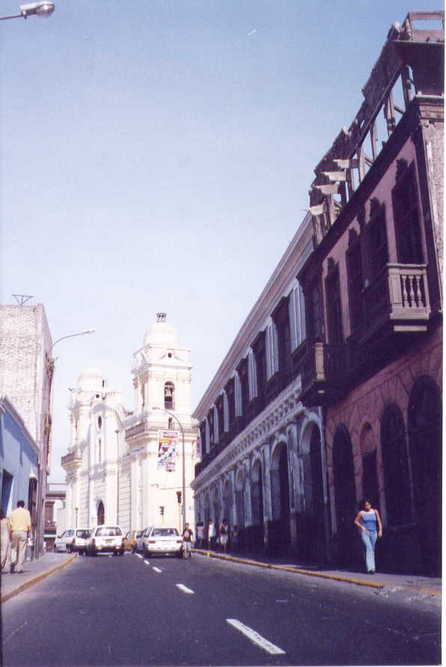

The Monastery of Santa Clara is located in one of the city's most feared areas: the ninth block of Jirón Ancash, in Barrios Altos. The enormous construction, bearing the title of Patrimony for Humanity, is untrustworthy. What is left of the Huatica River has dampened the foundations of the walls. The columns have begun to give way. The roof of the main church shows dozens of cracks.

Last year, Civil Defense ordered it closed. Since then, Mass is celebrated in the smallest chapel, and no one can enter besides the priest. If someone does, the Poor Clares will be fined.

Their resources are meager. Years ago, when Lima was a city of Viceroys and the nuns came from well-off families, donations supported the Monastery's upkeep. Now, that is no longer possible. In the surrounding area, residents live in overcrowded misery and the new postulants to the religious life come from the provinces.

Any time a painting or a piece of artwork from the 16th or 17th century needs to be restored, the nuns pray they will receive private donations.

At times, the remedy has been worse than the illness.

"Shoddy restorations have damaged some saints carved in wood," they say. During one of the most recent modifications, a floor lined with antique tiles from Seville was buried under kilos of cement. The foreman had thought the tiles were of no importance.

The monastery's most precious treasure is a sculpture of the Señor de Burgos. This image of Jesus Christ dates from the 18th century, and, as the legend goes, is there because it did not want to leave the day it was meant to be taken to Chile.

The Poor Clares say that during that time, Sor Jerónima de Jesús dreamt that Christ asked her to build a chapel for him. The next morning, an Augustine priest arrived at the Monastery with the sculpture of Jesus which he offered them for 400 pesos. The nuns only had 300. Despite their pleas, the priest would not accept the offer. However, according to the legend, when the priest tried to leave the monastery with the sculpture,the sculpture would not go out the door it had been brought in.

The history of this monastery includes a Peruvian nun of African descent, the venerable Ursula de Jesús. Originally a slave, she entered the monastery in order to help with the housework and ended up staying for the rest of her life. At the time, a black slave could not aspire to be a nun, but she possessed, "a very strong spirituality," says Sor Rosa. During her years in the Monastery, she gained renown as a visionary and is still venerated to this day.

This connection to their history makes the Poor Clares remain in Barrios Altos. Though they are threatened by the humidity that is eating away at the monastery, surrounded by the pollution of the city, the noise along Jirón Ancash, and the the rough nature of their neighborhood, known as Cinco Esquinas (Five Corners), the Poor Clares have rejected the Archbishop's request for them to abandon the convent and move to a different area. "We can not leave this place. There are many poor people here who need us. Our task is to be with them," says Sor Rosa.

New times, old traditions.

The only male in the convent is Bobby, "the watchdog that entertains himself playing with stones," says Sor Rosa. She entered the monastery when she was 17 years old. She has lived the past 13 years within these immense four walls. She has only gone beyond the walls in order to renew her National Identity Document, or vote.

Is it difficult to live a cloistered life? "No, we are always busy. We have so many chores to do. People think we are bored all day in here, but we also have fun. We play, we dance. Of course we do. This is the life we have chosen and we like it," she says.

Every day, dozens of people come to the monastery to ask for a piece a bread or a glass of water. No one can see the nuns, only hear them. The requests are made and given out through a revolving wooden window. Food is never denied here. Sor María says that as long as they have something to give, they will never deny anyone. "We are poor, but the people around here live in misery."

Stereotypes are swept aside when you meet the nuns. The Poor Clares are mostly young, smiling, and high-spirited. The day we visited, they were working in the garden. They wore their work aprons. They would not allow photos.

The ones who surely could not have been older than 20 told the photographer, "How can you take pictures of us like this? Allow us to fix ourselves up a little."

"A women never stops being concerned with her appearance, does she?" "Of course not," answered Sor Rosa. And in half jest (or maybe not) she added, "Every time we see a handsome man, we thank the Lord for having created such a beautiful creature. We are human beings, like everyone else."

In the past, cloistered life must have been more difficult. In the present, electronic media has improved communication. The concept of the cloister has acquired a different meaning. A century ago, in order to visit the monastery, the Archbishop would have had to grant permission. These are different times.

The.Flying.Gato@gmail.com

.

.

.

The police also stated, "If his sales were low, he would get angry and jump up and down on his one good leg. During the first few days of surveillance, we never suspected he had hidden the drugs inside the prosthetic leg. We thought his cronies had the merchandise."

The police also stated, "If his sales were low, he would get angry and jump up and down on his one good leg. During the first few days of surveillance, we never suspected he had hidden the drugs inside the prosthetic leg. We thought his cronies had the merchandise."